Researchers at Boston College published an article in the journal Science on Thursday that has spelled trouble for the state of the Earth’s glaciers amid a continually rising global temperature.

The survey called the finding of the retreat of Andean glaciers “unprecedented,” revealing that they had shrunk to their smallest size in more than 11,700 years.

Glacier Melt

Scientists have long predicted the consequences of global warming will extend to melting glaciers, but the rate of retreat the study found in four glaciers in the Andes Mountains still surprised researchers.

Boston Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Jeremy Shakun said that the glacial retreat has passed an alarming benchmark noting a possible epoch change.

Smaller Glaciers

Shakun concluded that researchers now have solid proof that the glaciers are much smaller than previously predicted.

“We have pretty strong evidence that these glaciers are smaller now than they have been any time in the past 11,000 years,” said Shakun who co-authored the report.

Tropic Glaciers

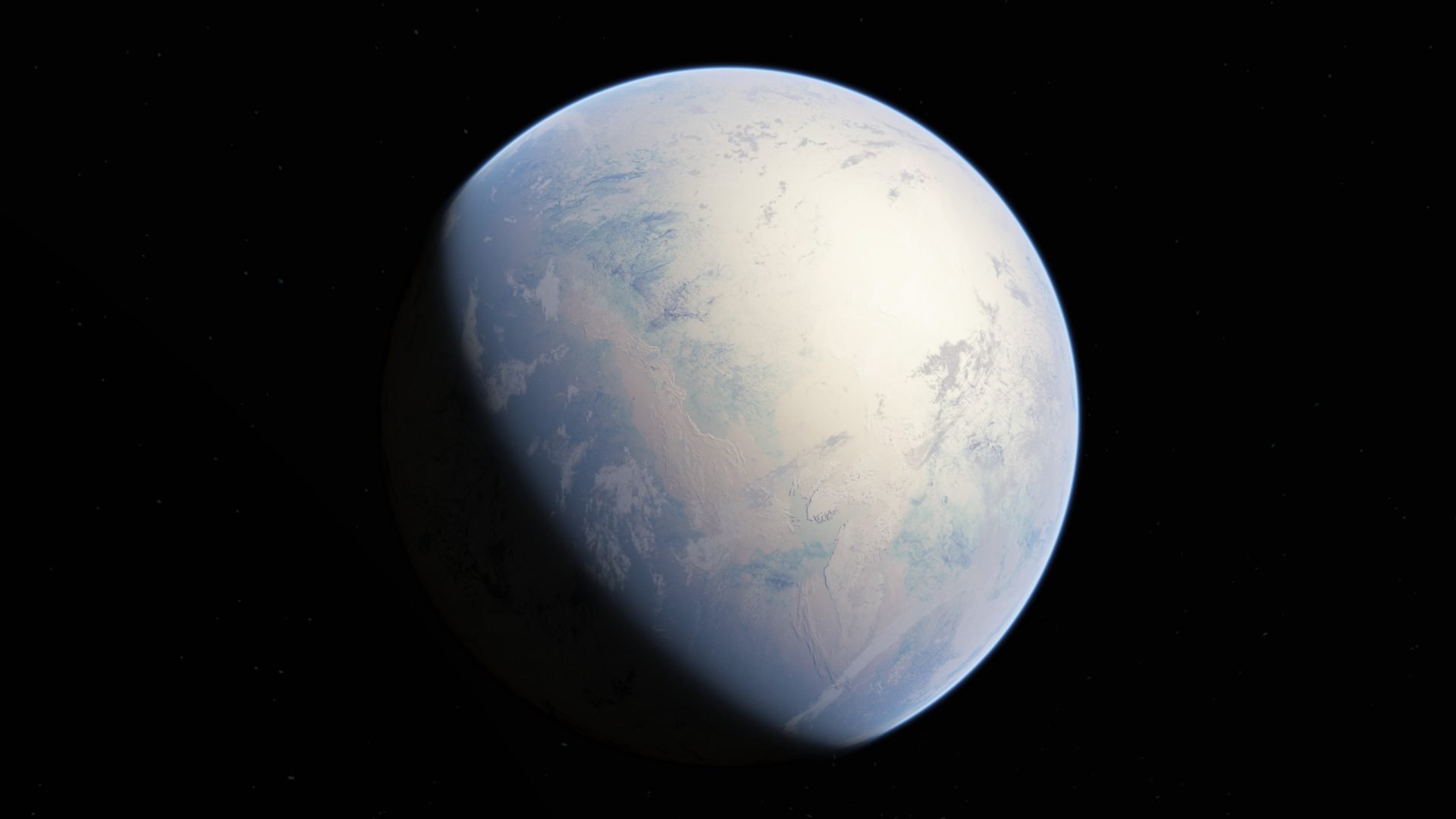

The glaciers in the Andes Mountains are known as “tropic glaciers,” meaning they exist in the regions near the equator of the Earth.

Because temperatures tend to be higher near the equator, tropic glaciers typically only occur in high mountain ranges where snow is unable to melt. However, as Earth’s temperature has been warming, tropic glaciers have become rarer, with only a few left in the world.

Epoch Change

Study researchers think the results indicate an epoch change, necessitating a transition from the Holocene interglacial period into the Anthropocene.

“Given that modern glacier retreat is mostly due to rising temperatures—as opposed to less snowfall, or changes in cloud cover—our findings suggest the tropics have already warmed outside their Holocene range and into the Anthropocene,” said Shakun.

Holocene Verus Anthropocene

Scientists categorize the history of the earth into different time periods, known as “epochs.” Currently, researchers estimate we are in the Holocene interglacial period and have been for approximately 11,700 years.

Some scientists consider the Holocene the last “natural” state of the Earth, which will eventually give way to the Anthropocene epoch characterized by “humanity-driven” environmental conditions.

Impact of Humans

Scientists still debate the use of the terms Holocene and Anthropocene as well as when it is appropriate to say that nature has ceased to be “natural” and more driven by human action. The International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) has not yet formally adopted the Anthropocene term.

Proponents of calling the current epoch “Anthropocene” say that humans now affect nature on an undeniable global scale. These proponents cite the acidity of the oceans, CO2 in the atmosphere, the populations of animals on the planet, weather patterns, and the rising global temperature as all being driven by human action. To them, this is evidence enough that the world has already transitioned from the Holocene epoch to the Anthropocene epoch.

Canary in the Coalmine

Shakun says the findings are notable because it is the first region in the world where scientists have found strong reason to believe that glaciers on the Earth have crossed the epoch benchmark.

“This is the first large region of the planet where we have strong evidence that glaciers have crossed this important benchmark—it is a ‘canary in the coal mine’ for glaciers everywhere,” said Shakun.

Natural Fluctuations

While glaciers on the Earth have been noted to be shrinking for over a century, researchers have been trying to determine just how much of this glacier retreat is due to natural fluctuations that might have also occurred at other times in the Earth’s history.

To answer this question in the study, Shakun and the research team examined the chemistry of rocks in the Andes mountains looking for rare isotopes to indicate how much cosmic radiation from space they contained.

Like Sunburn

Shakun likened this method of measuring isotopes in rocks to looking at a sunburn to determine how often a person gets sun exposure. This method effectively tells researchers how often huge glacier retreats like this happened in the past.

“By measuring the concentrations of these isotopes in the recently exposed bedrock we can determine how much time in the past the bedrock was exposed, which tells us how often the glaciers were smaller than today—kind of like how a sunburn can tell you how long someone was out in the sun,” Shakun said.

No Prior Exposure

By measuring the isotopes of beryllium-10 and radiocarbon-14 on four different tropic glaciers, the team was able to conclude that no significant exposure like this has happened since these glaciers formed.

“We found essentially no beryllium-10 or radiocarbon-14 in any of the 18 bedrock samples we measured in front of four tropical glaciers,” said study researcher Andrew Gorin, now a Ph.D. student at UC-Berkeley. “That tells us there was never any significant prior exposure to cosmic radiation since these glaciers formed during the last ice age.”

Future Research

Shaukun and his team hope to use the isotope measuring technique on more glaciers in the world, building a body of evidence that other researchers can examine about glacial retreat.

“Once we do that, then these studies can all be put together into a global perspective on the current state of glacier retreat,” said Shakun.