Physical traits can indicate if people are closely related. Look at siblings, and you’ll see similar characteristics in their features — possibly features they’ve inherited from their parents. Maybe they have their “mother’s eyes.”

Our understanding of genetics has improved our understanding of relatedness. A new study suggests that all people who have blue eyes may be very closely genetically related.

New Research

Research conducted by the University of Copenhagen delves into the origin of blue eyes in humans by examining the genetic underpinning of eye color.

Professor Hans Eiberg from the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine led the research that found that all blue-eyed people may have recently shared a common ancestor.

The OCA2 Gene

The study focuses on a mutation in the OCA2 gene. This is a gene responsible for producing melanin.

Specifically, the gene codes for P protein is crucial in melanin production. Melanin is the pigment that gives color to our skin, hair and, of particular relevance to this study, our eyes.

Brown Eyes by Default

Research suggests that originally all human beings had brown eyes, Professor Eiberg says in the study.

Variations in eye color from brown to green can all be explained by different amounts of melanin in the iris. So, variation in eye color between people is basically simply indicating a variation in melanin.

Limited Blue Eye Variation

The story is a little bit different for blue-eyed people. There is only a tiny amount of variation in the amount of melanin in the eyes of all people with blue eyes.

It is this limited variation that indicates this recent common ancestor. In Professor Eiberg’s own words: “From this we can conclude that all blue-eyed individuals are linked to the same ancestor.”

Inherited a ‘Switch’

Professor Eiberg continues: “They have all inherited the same switch at exactly the same spot in their DNA.”

Conversely, brown-eyed individuals have a lot more variation in the part of their DNA code that is responsible for controlling the production of melanin. The “switch” that Einberg refers to is a mutation of the OCA2 gene.

OCA2 Mutation

The University of Copenhagen study describes a genetic mutation that affects the OCA2 gene in the human chromosome.

This mutation, as described by Professor Eiberg, basically created a “switch” that essentially “turned off” the ability to produce brown-eyed people by impacting the gene coding for melanin production, which is the reason for brown eye coloring.

Not Strictly an Off Switch

This mutation and the “switch” it creates doesn’t turn off the OCA2 gene entirely. A total lack of melanin in the hair, skin and eye color of humans does happen in a condition known as albinism.

Instead, the mutation, located in a gene adjacent to the OCA2 gene, limits its action.

Diluting Eye Color

The switch limits the action of the OCA2 gene, which in turn reduces the amount of melanin produced in the iris.

Essentially, this mutation dilutes the standard human brown eyes down to blue. It’s a very specific genetic action, which again points to a shared origin of the nutation for all blue-eyed people.

A Shared Switch

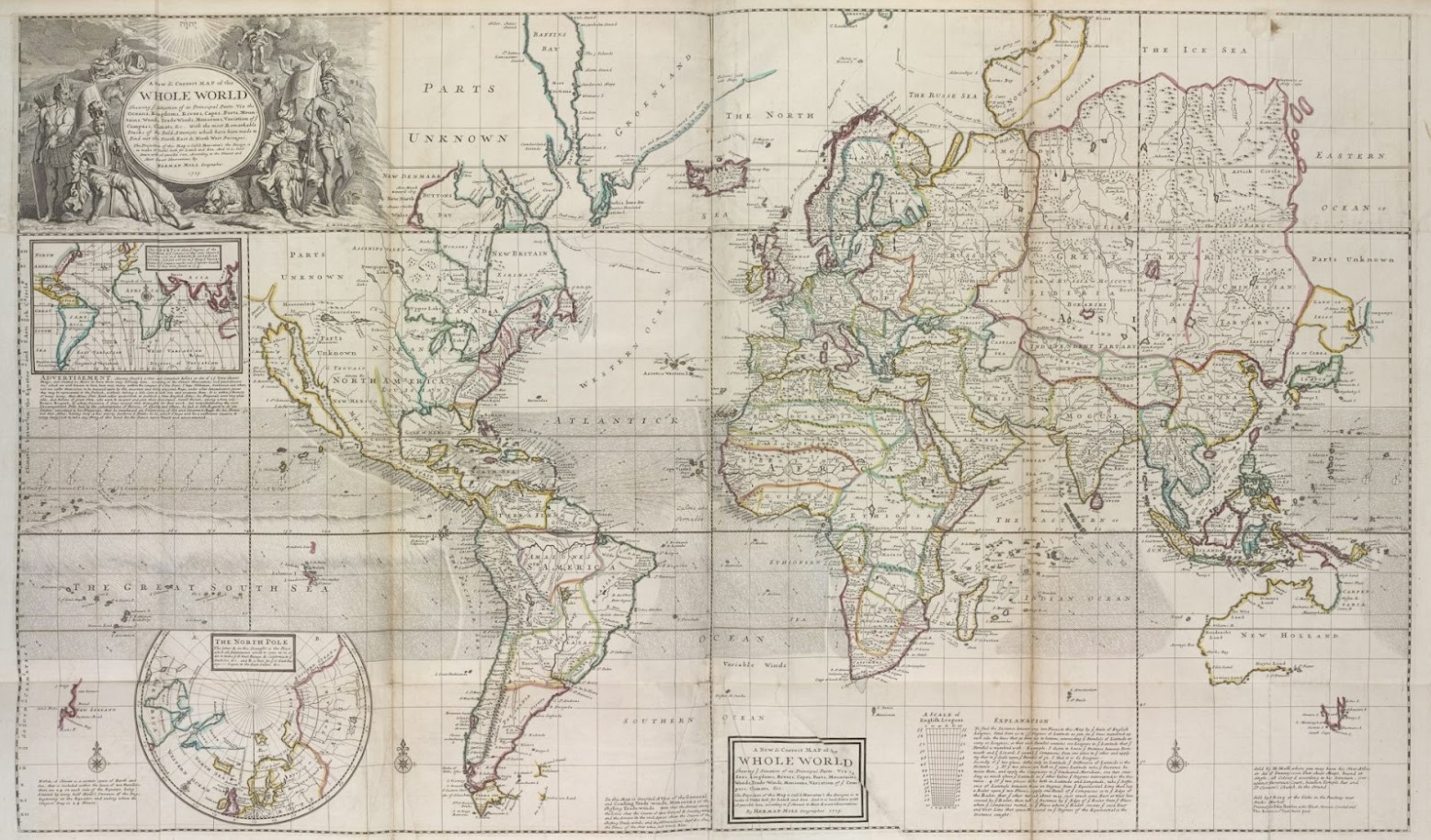

The Copenhagen research team looked at the mitochondrial DNA of blue-eyed people from a diverse range of countries, from Jordan to Denmark to Turkey, and also compared their eye colors.

The findings, which mark the latest in Professor Eiberg’s decades of research into the OCA2 gene and eye color, identify a genetic mutation from 6,000 to 10,000 years ago that’s responsible for every single blue-eyed individual alive on the planet today.

Origins of the Mutation

The mutation is believed to have originated in the Black Sea region of Europe in this period 6,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Low sunlight levels in the area may have created a selection pressure for low melanin, making fair hair and light skin more beneficial. So the blue-eyed variation propagated and spread across Northern Europe.

How Nature Can Shuffle Our Genome

This blue-eyed mutation is not something that is either positive or negative in terms of survival advantage, it is just a naturally occurring variation.

As Professor Eiberg puts it: “It simply shows that nature is constantly shuffling the human genome, creating a genetic cocktail of human chromosomes and trying out different changes as it does so.”